La Fundación Aranzadi LA LEY lanza Mujeres por Derecho con motivo del Día de la Mujer, una selección de artículos de juristas que destacan cómo la igualdad enriquece y democratiza la sociedad. En esta iniciativa participa Alicia Muñoz Lombardia, miembro del Patronato de Womyc. Desde abril de 2021, más de 300 mujeres han participado, consolidando este foro como referente en el debate sobre el papel femenino en el ámbito jurídico. https://www.legaltoday.com/actualidad-juridica/mujeres-por-derecho/malos-tiempos-para-el-feminismo-2025-03-10/

Why are girls not interested in science?

Last year, the UNESCO published a report entitled “Cracking the Code: girls’ and women’s education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)” which can be downloaded from (https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000253479). In this report, they examined the factors that influence girls’ and women’s participation, performance, and retention in STEM education, and consider how the education sector can effectively foster their interest and involvement in these fields. In their report, they found that women remain underrepresented in STEM fields, making up only 22% of the workforce in these fields across G20 countries. This only represents a 3% increase since their previous report in 2021.

A significant concern in many countries is not only limited numbers of girls going to school but also limited educational pathways for those that step into the classroom. This is reflected by the fact that only 35% of STEM graduates are women and this can drop to just 26% in engineering. In their report they found that the degree of gender equality in wider society influences girls’ involvement in STEM. For example, in those countries with greater gender equality, girls tend to perform better in mathematics and the gender gap in obtaining high marks in the subject is smaller. Importantly, gender stereotypes presented in the media are often absorbed by both children and adults, shaping their self-perception and views of others. The media has the power to either reinforce or challenge biased ideas about who is suited for STEM skills and careers. In order to increase girls’ and women’s interest in, and engagement with, STEM education a series of interventions including some at individual, family, school and societal level have been developed.

To promote the development of positive STEM identity at an individual levels, girls should be exposed to STEM experiences. In support of this, the UNESCO together with the Government of Kenya, the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) and the University of Nairobi organize annual Scientific Camps of Excellence for Mentoring Girls in STEM which are focused on demystifying stereotypes.

From early ages, girls and women receive comments in their families that can make them think science is not for them. To overcome this problem, awareness-raising campaigns targeting parent’s perceptions have been carried out in some countries alongside significant improvements to STEM education. Teachers also need to understand why their girl students do not want to pursue a career in STEM. TeachHer is an UNESCO initiative focused on generating gender-responsive lesson plans and inspiring teenagers to pursue STEM careers this can be done for example by the creation of classroom environments that fosters interests in STEM via project-based learning.

Policies can also have a positive impact in the participation of girls in STEM. For example, in Germany the government has developed a National Plan to address gender gaps in STEM education and employment.

Despite all these efforts, low female participation in STEM is still a fact. Broader efforts are needed to advance gender equality in STEM. Some of the ongoing interventions alongside the development of programmes that address teacher’s perception to implement a deliver a gender-responsive curricula can be the basis to increase the interest of girls in STEM.

When is a good time?

A couple of years ago, Sarah Thébaud and her colleagues published a study where they found that motherhood affects women’s careers in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) long even before they are to become mothers. According to their data which is based on interviews to 57 PhD students, motherhood is seen as a subject of fear, repudiation, and even public controversy. It is estimated that about 43% of women leave their full-time jobs in STEM after giving birth their first child compared to 20% of men. Moreover, parenthood is in many cases pushed back until tenured. Therefore, parenthood plays a significant role in the gender imbalance within STEM employment, as both mothers and fathers seem to struggle with balancing caregiving responsibilities and their careers in STEM. But, is there a right time for parenthood?

Earlier this year, Julian Nowogrodzki wrote an article in Nature where he interviewed 5 PhD students who became parents during their training. There is no doubt that becoming a parent while doing a PhD would entail sacrifices in terms of scientific productivity. But from the article it was clear that for some of these students who decided to be parents during their PhD it was just the perfect time because of the flexible PhD schedule. It is worth mentioning that experiences and considerations vary significantly depending on the institutions where the research is carried out as well as the individual research groups. Moreover, there are still some instances where parental leave policies do not apply for PhD students.

To facilitate parenthood in STEM fields we believe that workplaces should offer flexible work arrangements, paid parental leave and on-site or subsidized childcare. Career progression should be also supported through this period via tenure clock extensions, re-entry programs, mentorship, and fair promotion criteria. Institutional research culture, such as normalizing parenthood, increasing leadership representation, and reducing hiring biases, are also essential. We further believe that fostering parent support networks, providing childcare at conferences, and collaborating with institutions can help create a more inclusive environment. These efforts ensure that STEM professionals don’t have to choose between their careers and parent.

References:

Thébaud, S., & Taylor, C. J. (2021). The Specter of Motherhood: Culture and the Production of Gendered Career Aspirations in Science and Engineering. Gender & Society, 35(3), 395-421. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211006037

Nowogrodzki J. PhD parents: the pros and cons of having a child during your doctorate. Nature. 2025 Jan;637(8046):749-751. doi: 10.1038/d41586-025-00058-7. PMID: 39806109.

¿Cuándo es un buen momento?

Hace un par de años, Sarah Thébaud y sus colegas publicaron un estudio en el que descubrieron que la maternidad afecta las carreras de las mujeres en ciencia, tecnología, ingeniería y matemáticas (STEM) mucho antes de que se conviertan en madres. Según sus datos, basados en entrevistas a 57 estudiantes de doctorado, la maternidad se percibe como un tema de miedo, rechazo e incluso controversia pública. Se estima que aproximadamente el 43% de las mujeres abandonan sus trabajos de tiempo completo en STEM después de dar a luz a su primer hijo, en comparación con el 20% de los hombres. Además, la paternidad en muchos casos se pospone hasta obtener la titularidad. Por lo tanto, la paternidad juega un papel significativo en el desequilibrio de género dentro del empleo en STEM, ya que tanto madres como padres parecen tener dificultades para equilibrar las responsabilidades de cuidado con sus carreras en estos campos. Pero, ¿hay un momento adecuado para la paternidad?

A principios de este año, Julian Nowogrodzki escribió un artículo en Nature en el que entrevistó a cinco estudiantes de doctorado que se convirtieron en padres durante su formación. No hay duda de que convertirse en padre mientras se realiza un doctorado conlleva sacrificios en términos de productividad científica. Sin embargo, en el artículo quedó claro que para algunos de estos estudiantes, que decidieron ser padres durante su doctorado, fue el momento perfecto debido a la flexibilidad del horario del doctorado. Vale la pena mencionar que las experiencias y consideraciones varían significativamente dependiendo de las instituciones donde se lleva a cabo la investigación, así como de los grupos de investigación individuales. Además, todavía existen algunos casos en los que las políticas de licencia parental no se aplican a los estudiantes de doctorado.

Para facilitar la paternidad en los campos STEM, creemos que los lugares de trabajo deberían ofrecer arreglos laborales flexibles, licencias parentales pagadas y guarderías en el lugar de trabajo o subsidiadas. La progresión en la carrera también debe ser apoyada durante este período a través de extensiones del reloj de titularidad, programas de reingreso, mentoría y criterios de promoción justos. La cultura institucional de investigación, como la normalización de la paternidad, el aumento de la representación en liderazgo y la reducción de los sesgos en la contratación, también es esencial. Además, creemos que fomentar redes de apoyo para padres, proporcionar cuidado infantil en conferencias y colaborar con instituciones puede ayudar a crear un entorno más inclusivo. Estos esfuerzos aseguran que los profesionales de STEM no tengan que elegir entre sus carreras y la paternidad.

Referencias:

Thébaud, S., & Taylor, C. J. (2021). The Specter of Motherhood: Culture and the Production of Gendered Career Aspirations in Science and Engineering. Gender & Society, 35(3), 395-421. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211006037

Nowogrodzki, J. PhD parents: the pros and cons of having a child during your doctorate. Nature. 2025 Jan;637(8046):749-751. doi: 10.1038/d41586-025-00058-7. PMID: 39806109.

A step towards more inclusive Gender representation in Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology conferences

Since 2018 the initiative #DóndeEstánEllas (#WhereAreThey?) led by the European Parliament Office in Spain has been recording speaker participation in events related to European affairs. This initiative aims to avoid all-male panels in conferences and to provide visibility and encourage participation of women in these events. In science, attending and presenting research data in conferences is critical for the dissemination of research findings. These conferences also provide invaluable opportunities for networking, collaboration and visibility to speakers, all factors which are critical for career progression. However, a detailed understanding of gender and geographical representation in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology conferences was lacking.

A recent study led by Katharine Last and published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases shows that women were equally represented that men in speaker sessions in both the ID week (2016-2021) and the ECCMID conferences (2016-2023). However, women were under-represented as chairs (28 [30%] out of 92 vs 1362 [48%] out of 2830) and speakers (17 [27%] out of 63 vs 946 [44%] out of 2148 ) during prestigious plenary keynote lectures at ECCMID alone. On the contrary, 60% of speakers at the “year in…” session during ECCMID were women (26 out of 43 vs 837 out of 2168).

In these sessions, one speaker provides with an overview of the most important publications in the past year in the field, but they are not required to present their own work. Importantly, this study also shows that only 11% of the speaker and chair positions were held by attendees from low-middle income countries. However, one of the main limitations of the study is that gender and geographical representation was only recorded for a limited number of sessions and a systematic analyses of these should be carried out to corroborate findings.

Gender equity initiatives have been implemented by organising committees of research conferences across scientific and other fields in the last few years. These approaches, allow organising committees to identify representation inequities and invite researchers from under-represented groups. Ensuring fair representation across various speaker demographics at conferences, particularly in speaker roles and high-profile sessions, demands intentional effort at both the professional society and conference program committee levels.

Reference:

Last K, Hübsch L, Marcelin JR, Huttner A, Cevik M, Papan C. Gender and geographical representation at infectious diseases and clinical microbiology conferences. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024 Mar;24(3):e153-e154. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00824-1

Avances hacia la igualdad de género en los Congresos de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Médica

Desde 2018, la iniciativa #DóndeEstánEllas promovida por la Oficina del Parlamento Europeo Española ha analizado el género ponentes en eventos europeos. Esta iniciativa tiene como objetivo visibilizar la composición de los paneles para evitar que la participación sea mayoritariamente masculina fomentando la presencia femenina en estas.

Una de las formas predominantes para difundir la investigación es la presentación de los hallazgos en Congresos y Conferencias. La visibilidad que estas reuniones ofrecen a los moderadores y ponentes es crucial para consolidar las carreras científicas. Además, estas actividades ofrecen oportunidades para establecer redes de colaboración. En el campo las enfermedades infecciosas y microbiología clínica no existen trabajos que analicen el género y el origen geográfico de de ponentes y moderadores.

Un estudio reciente de Katharine Last publicado en The Lancet Infectious Diseases indica que las ponencias tuvieron una representación de género igualitaria en las conferencias ID week (2016-2021) y ECCMID (2016-2023). Sin embargo, hubo menos moderadoras (28 [30%] de 92 vs 1362 [48%] de 2830) y ponentes (17 [27%] de 63 vs 946 [44%] de 2148 ) en las charlas plenarias del ECCMID. En cambio, en la sesión “Año en…” del ECCMID el 60% fueron mujeres (26 de 43 vs 837 de 2168).

Estas sesiones proporcionan una visión resumida de las publicaciones más destacadas del año, por lo que los protagonistas no hablan de su trabajo sino del de otros. En cuanto a la representación geográfica hay que destacar que solo el 11% de los ponentes y moderadores provenían de países de ingresos bajos y medianos. Sin embargo, solo se incluyó el análisis de género y geográfico de un limitado número de sesiones. Esta limitación debería ser subsanadas con estudios más sistemáticos.

En los últimos años, las comités organizadores de diversas conferencias han tenido en cuenta la equidad de género. Se han efectuado estudios que permiten a los comités organizadores identificar desigualdades de género entre ponentes y moderadores lo que permite ir eliminado la desigualdad tanto de género como geográfica. El papel de las Sociedades y de los comités organizadores y científicos en la consecución de estos objetivos.

Equality through Research

Sexism in academia is bad for science and a waste of public funding

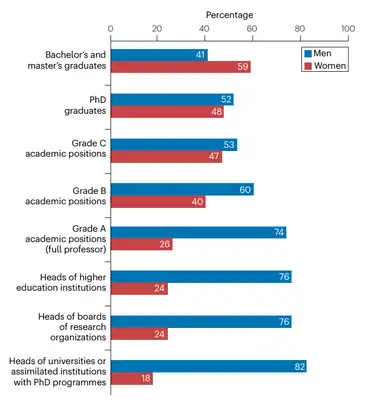

Higher education and research institutions are critical to the well-being and success of societies, meaning their financial support is strongly in the public interest. At the same time, value-for-money principles demand that such investment delivers. Unfortunately, these principles are currently violated by one of the biggest sources of public funding inefficiency: sexism.

The paper addresses the significant issue of sexism in academia, highlighting its detrimental impact on science and the wastage of public funds. It emphasizes the gender gap’s economic and scientific toll, suggesting reforms for academic efficiency. The paper discusses the attrition of women at various career stages due to discriminatory practices and the need for systemic changes to promote gender equity in academia. It calls for action from academic institutions, governments, and funding agencies to ensure transparency, accountability, and the dismantling of structural biases to improve science and provide value for money.

Read article from Nature